“Hacking” with Social Media

Published:

As part of a panel discussion on ‘Social Media and its Impact on Data Privacy for Corporates and Employees’ held during the World Economic Forum in Davos, Jan 2018, I was asked to provide some insights into how one might obtain compromising private information from social media.

Ever wonder just how much private information can be acquired from your social media accounts? Aside from the obvious of course - I’m sure we’re all heard the usual cautionary advice such as ‘remove geotags from photos’, ‘don’t share upcoming holidays’ and the (hopefully) blatantly obvious, ‘don’t post photos of your bank details’. But, unfortunately, that doesn’t seem to be enough. In recent years, we have seen Elon Musk sharing his personal mobile on Twitter, a VP at Hewlett-Packard revealing company secrets through his LinkedIn profile, as well as a rise in teens sharing their school names, email addresses, and even phone numbers over Facebook and Twitter.

There is a lot that can be scraped from the images we post online, and it doesn’t take a ‘hacker’ to gather all this information. I want to provide a quick breakdown on how someone with even minimal technical skills would be able to achieve this in the hope that it makes us all more wary of what we choose to post online.

Scraping Social Media

To begin with, there is a wealth of free and open source libraries and software that can already do the bulk of the work, as well as online tutorials that show you how to scrape social media, search for and extract relevant information. As an example, I have chosen to use Twitter’s API and a python-based client to interact with it - tweepy. With just a few lines of code, I was able to download over 500 images under tags relating to ‘work’ in the last year (though it is possible to download more, the api limits the return to 200 tweets).

tags = ['#atwork', '#intheoffice', '#inoffice', '#working', '#attheoffice']

for tag in tags:

for tweet in tweepy.Cursor(api.search,q=tag,count=200,

lang="en",

since="2017-01-20").items():

for media in tweet.entities.get("media",[{}]):

if media.get("type",None) == "photo":

image_content=wget.download(media["media_url"], 'twitter_images')Extracting Relevant Images

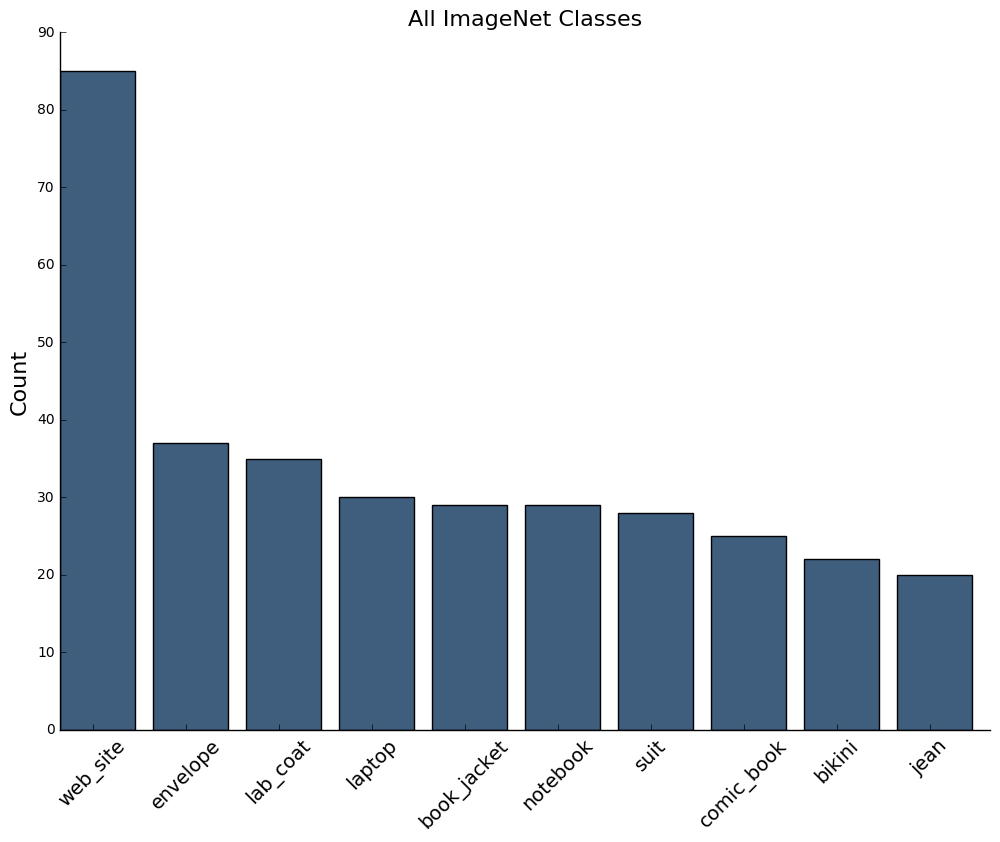

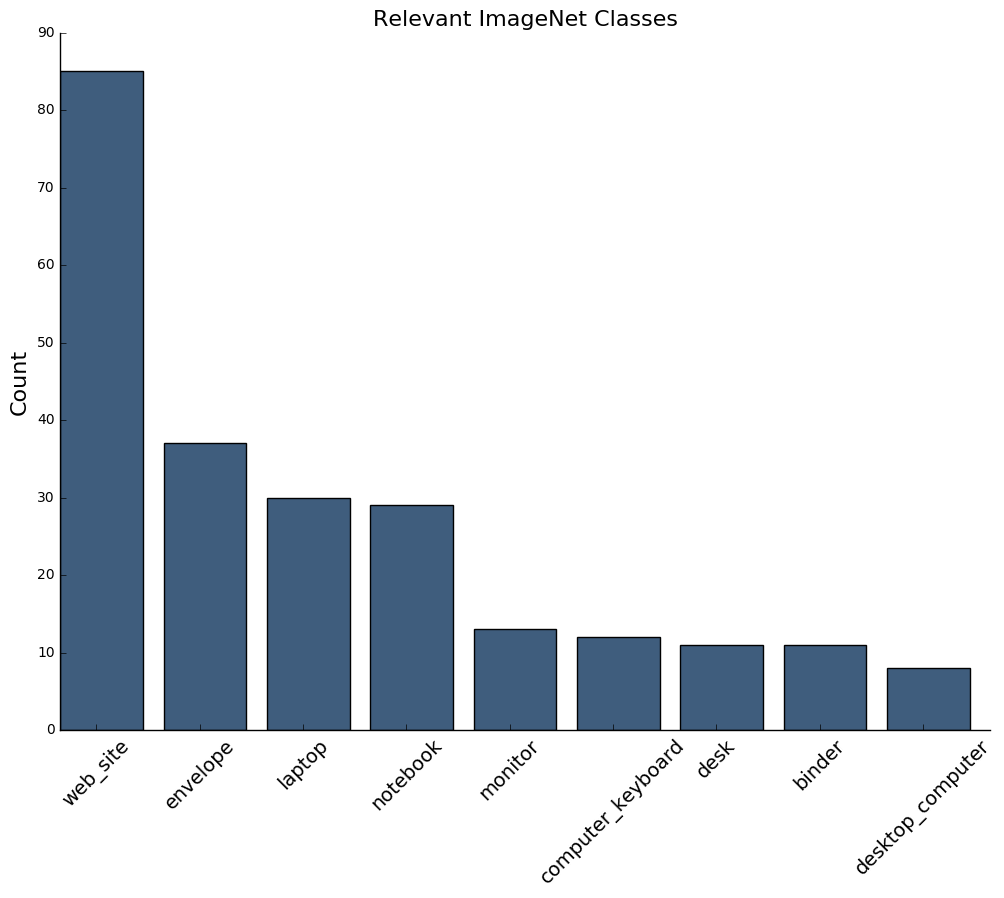

Using the current state-of-the art in machine learning models for object classification, I used the ResNet50 pre-trained on the ImageNet dataset to extract all the images classified as objects relating to computers and notes:

from keras.preprocessing import image

from keras.applications.resnet50 import ResNet50, preprocess_input, decode_predictions

model = ResNet50(weights='imagenet')

classes = ['monitor', 'computer', 'computing_machine',

'computing_device', 'notebook', 'web_site',

'computer_keyboard', 'laptop', 'binder',

'desktop_computer', 'desk', 'paper', 'envelope']

images = []

for im in os.listdir('twitter_images'):

img = Image.open('twitter_images/' + im)

preds = predict(model, img, target_size)

for i, c, p in preds:

if c in classes:

images.append(im)Again, you can use a number of open source machine learning libraries and models. I chose to use the keras neural network library with TensorFlow backend as it allows for easy experimentation with common models and datasets. The function predict return the top 3 classes as predicted by ResNet50.

Here are the most common predicted classes:

|  |

I noticed that a large number of images were stock photos, presumably taken from thumbnail images of posted articles:

|  |  |

Twitter is quite often used for sharing links as opposed to personal photos, so perhaps Instagram would have been a better bet, but let’s see whether we can still extract something interesting…

Extracting Private Information

This is the trickiest part to automate. At this stage, it is probably equally effective to go through the images by hand and look for any compromising information, such as open email inboxes, any identifiable company information such as logos, post-its or notebooks with passwords written on them. With such a variety, it’s hard to make machine learning algorithm that can detect them all without being specific about what we are looking for.

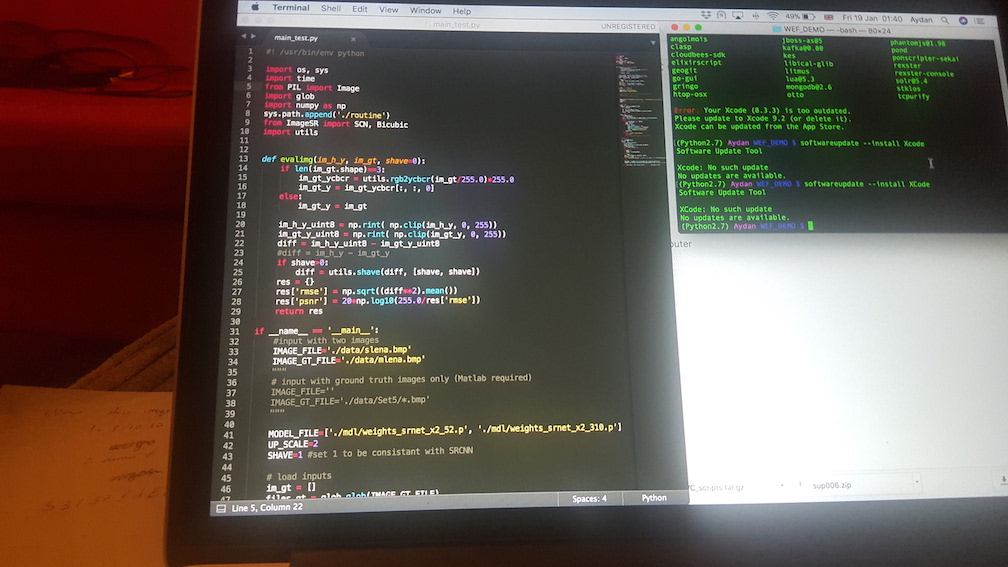

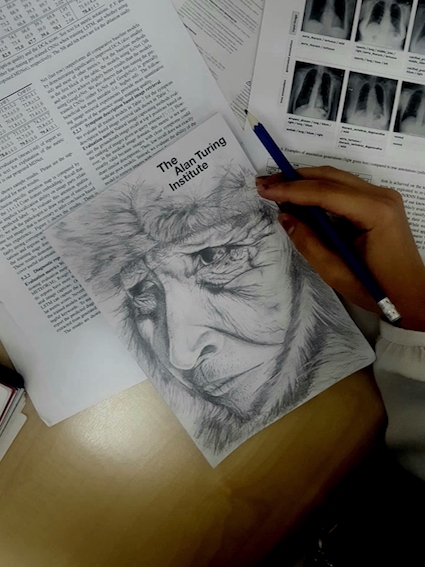

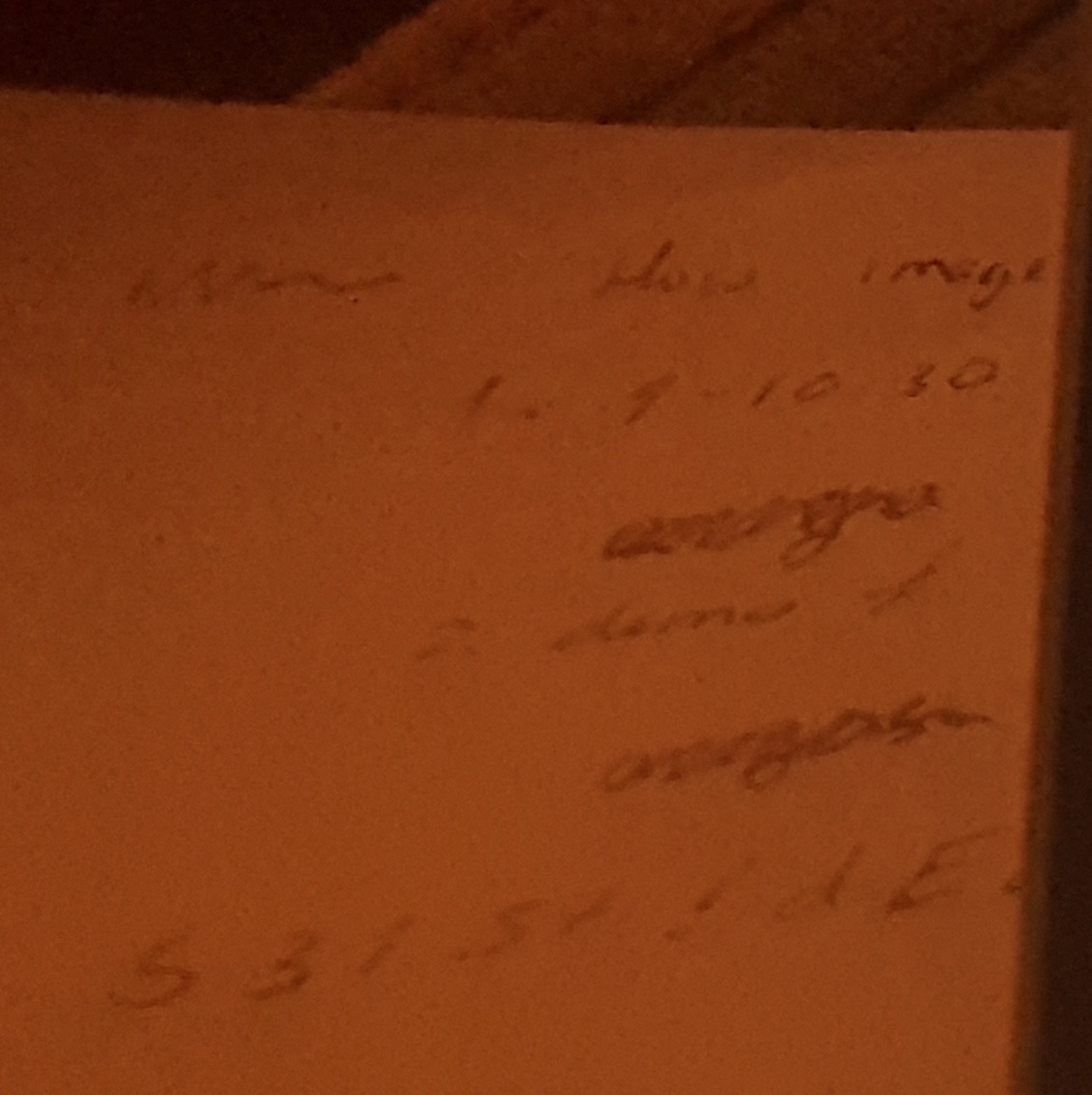

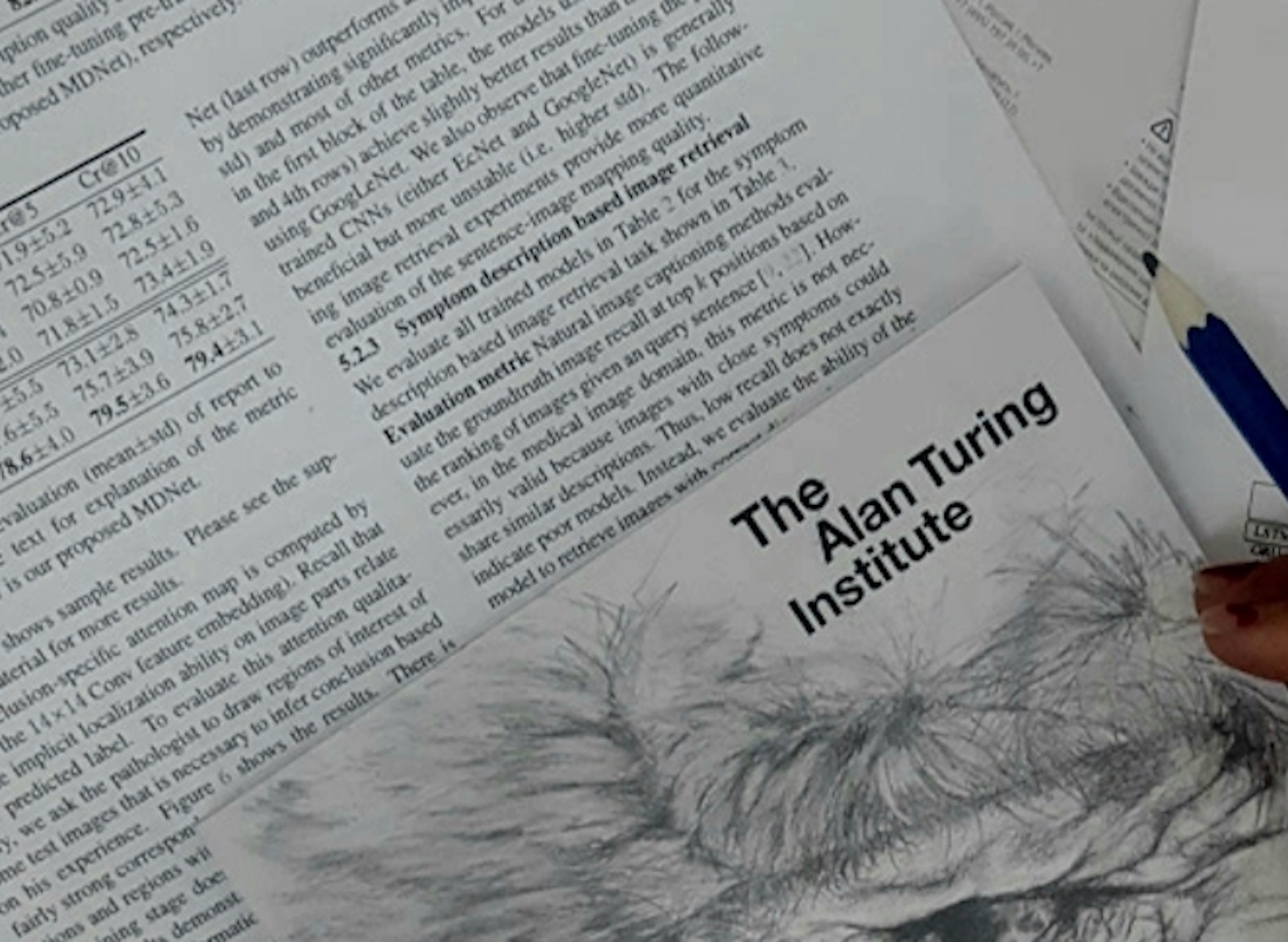

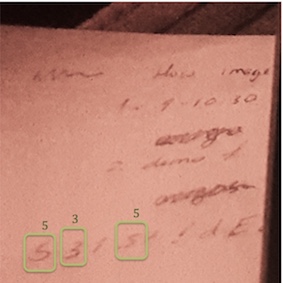

For instance, we may be looking for any piece of handwriting which may be a password. Various character/digit recognition as well as handwriting detection tools exist that can do this. For the purposes of this demo, I have used some of my own photos that I took at work (one of which I genuinely posted to Instagram), and zoomed in on the potentially compromising information.

|  |  |

|  |  |

These images contain information pertaining to my name, my place of work, the topic of my research, date and time of a meeting, and what looks like a series of characters which may be a password (obviously it’s not real, but I do occasionally write my passwords on scraps of paper by my monitor as I’m sure many people do).

Enhance

With the quality of phone cameras these days, even blurry images of handwriting in a darkly lit room can still be deciphered. If not, there are always free, online tools and libraries that allow you to ‘enhance’ your photos, for instance, Let’s Enhance, or the recently published Pixel Recursive Super Resolution from Google Brain. These state-of-the-art machine learning models (deep convolutional neural networks) are trained on blurred images and their full-resolution counterparts, thereby learning to ‘upsample’ blurred images.

Detect

One simple thing to look for in an image is digits. Digits can mean dates, times, phone numbers and passwords, and there is already quite a lot of research that uses the MNIST digit recognition dataset as a benchmark, which means that these machine learning algorithms are tailored to recognise hand-written digits.

Your Private Information is now Public

Going through just a few of the Twitter images, I came across a number of the following:

- Full names and other social media usernames. This may not seem alarming, but once you can link up all the social media accounts belonging to one person, they become much easier to track down and doxx.

- Phone numbers. This is perhaps more alarming. It seemed that one person in question didn’t realise their phone number was being shared by posting a screenshot of a text conversation, but it was very much readable.

- Exact locations, either by ‘checking in’, posting screenshots of weather at the location, or photos of street signs from Pokemon Go. Again, not a danger on its own, but alongside other information, can make you very easy to locate.

- Medical history. I’m not sure what the intention was with this one, but someone posted their medical results alongside their name.

- What they are working on, and for which company. Whilst the majority of companies would not mind you openly talking about your work, posting the precise details, especially if you’re working on proprietry material, would certainly be frowned upon, if not grounds for dismissal. One person had their screen open to a database containing keywords such as ‘Bank Rex Data’ and ‘Cheque Fwd Address’.

- Personal calendar. What’s more useful than posting your location? How about the precise date and time that you will be there.

So what can I realistically do with all this information?

At the moment? Not a whole bunch. But this is only an afternoon of work, and 500 images from Twitter. Collecting an aggregate of all the types of private information I found for each user would be far more useful, and certainly do-able using the methods I described. Stealing someone’s identity is then a series of steps linking up that information:

- Names, places of work and open computer screens can get you their email address.

- Next, you go down the rabbit hole of ‘reset passwords’. Some are not as secure as others, especially older email clients. Some password recovery features ask you to answer a few questions, such as your date of birth, home town, post code/zipcode, phone number.

- You usually only need to ‘hack’ one email address - the rest will fall like dominoes. These days, most people use an email address as their password recovery tool - giving you access to not only their emails, but any other accounts which they have registered using that email address.

- The rest is fairly straightforward - you now have means to go as far as reseting the passwords on the bank accounts. Here is just one example where they do just that.